These ads are poisoning trust in media

‘Native advertising' allows fossil fuel companies to disguise their ads in news outlets. A new book argues the practice undermines journalistic credibility.

“There is no need for advertisements to look like advertisements,” the “father of advertising” David Ogilvy wrote in 1963. His global ad agency went on to create campaigns for oil giant BP, including helping it coin the slogan “Beyond Petroleum” as part of a rebranding effort.

“If you make [advertisements] look like editorial pages, you will attract about 50 per cent more readers,” Ogilvy claimed. “You might think that the public would resent this trick, but there is no evidence to suggest that they do.”

A new book out this week, Content Confusion: News Media, Native Advertising, and Policy in an Era of Disinformation, finds that Ogilvy got it wrong. Author Michelle Amazeen compiles her and others’ research on “native advertising,” a practice where corporations work with in-house content studios at news outlets to create ads that are designed to look and feel just like the publication’s journalistic articles. The book delivers a stark warning to outlets that native ads are eroding the public’s trust in media and poisoning the role of journalism in democracy.

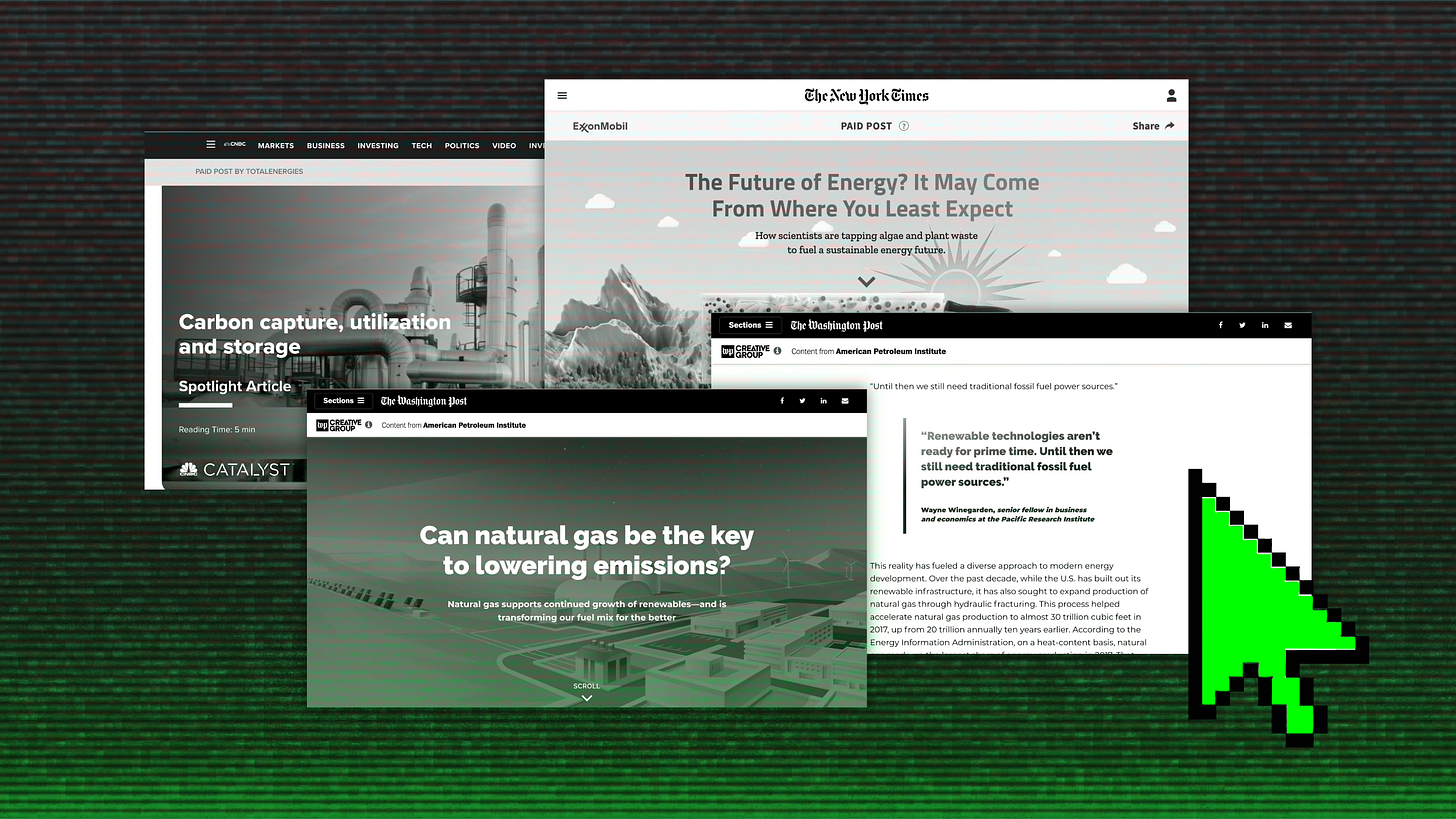

Many of the native ad campaigns documented by Amazeen, a researcher and professor at Boston University, were created by mainstream media outlets on behalf of major oil companies and their trade associations over the past decade. The campaigns often advertise controversial technologies like carbon capture as climate solutions, portray fossil fuel companies as climate-friendly, or misrepresent their role in the energy transition.

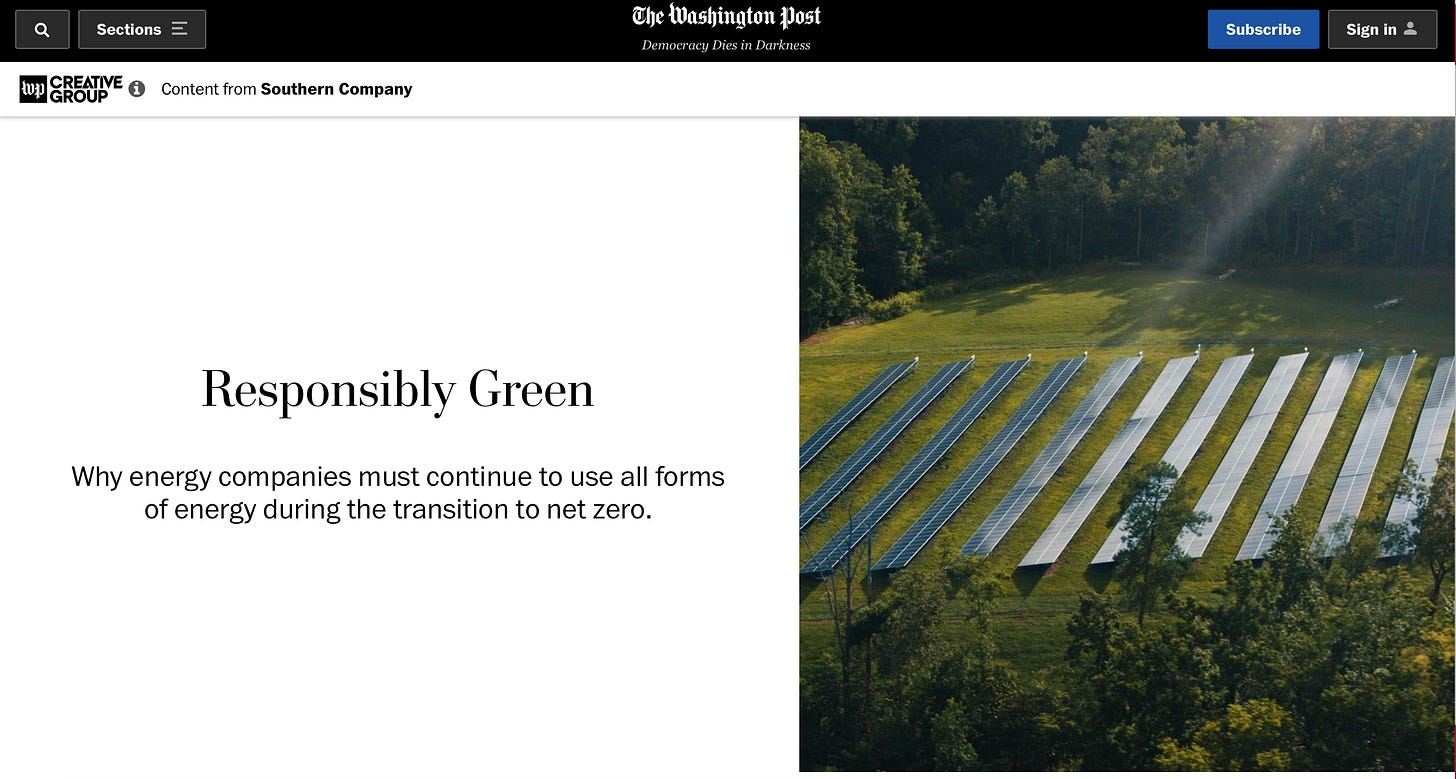

In some cases, outlets run native ad campaigns for corporate clients that undermine their own journalism. One such native ad created by the Washington Post’s content studio claims utility Southern Company is helping to lead the energy transition, despite their role in blocking it and ramping up their reliance on fossil fuels. It also claims energy demand can’t be met by renewables alone, even while the Post’s own reporting demonstrates how transitioning to all renewables can actually decrease energy demand.

Another native advertisement for Exxon created by the New York Times’ T Brand studio as part of its “Unexpected Energy” campaign touts the company’s research into algae biofuels and still runs on their website — even though Exxon dropped its algae research years ago. In an award application obtained during a congressional investigation, media and ad agency Universal McCann wrote that it worked with the T Brand Studio to replicate the “Timesian” voice in order to “mirro[r] the award-winning journalism of the world-renowned publication.” The campaign set out to combat “a volatile news cycle [that] often owns the share of voice, not always providing an accurate depiction of ExxonMobil.”

T Brand Studio’s creation of that algae advertisement was not mentioned in the Times’ own coverage of Exxon’s other algae ads, part of its reporting on another congressional investigation into climate disinformation.

“Here then, we have evidence that the Times can be bought so that its branded messages are, indeed, meant to compete against its news agenda,” Amazeen writes.

Amazeen’s prior studies have found that readers almost always confuse such ads with real reporting. That confusion comes partly from a lack of standardized disclosure language clarifying the post was a sponsored ad, which is sometimes not detected by readers at all. The problem only worsens when the posts are shared on social media, where disclosures required by the Federal Trade Commission often disappear entirely.

“We’re in a time right now where it’s so hard to tell the provenance of so much of what we see online or and whether it’s authentic or not,” Amazeen said, pointing to the proliferation of AI-generated content. “Theoretically, news orgs are supposed to be the bulwark against all this fake stuff, but they’re contributing to the problem and compromising themselves.”

Through conversations, polling, and survey responses, Amazeen found that when readers do realize they’ve been served a native ad by a news outlet, they often become angry and lose faith in any content coming from that publication — even when it’s true journalism. Those responses indicated that people are more resentful of the publication than the advertiser.

“I’m tired of the news being owned by corporations,” one reader wrote in response to a social media post of a real native ad created by the T Brand Studio for Exxon. “Why is The NY Times pushing Exxon ads as if they are real posts… NY Times has no principles. They only care about money,” wrote another.

That consumer backlash “hurts the publications, not the advertiser, because news consumers see the publication as promulgating fake news,” Amazeen writes.

Jill Abramson, a former executive editor at the New York Times, said she was disturbed by the Times’ decision to run native ads. “I saw that, and still see it, as deliberately causing confusion among readers and viewers of mainstream news,” she said.

Apart from worrying whether readers were being deceived, Abramson was concerned about the impact on journalists, who might not be comfortable with an in-house ad agency at the outlet. She also said she opposed a policy that allows people working for the Times’ advertising division to write news for the paper after a year-long “cooling-off period.”

News outlets often claim there are strict barriers between their editorial and advertising teams. But “that proverbial wall is much more porous than outlets let on,” Amazeen said. She spoke with marketing strategists at those content studios, who told her they ask journalists to share information about the stories the editorial team is working on in meetings with corporate clients. She also found that the ads are frequently written by former journalists themselves, some of whom are sought out for hire by media content studios after facing layoffs at corporate outlets.

Amazeen explains how corporations first realized that “advertising could be used to sell more than mere products” — it could “shape cultural sentiment, social values, and political ideologies.” In the 1970s, fossil fuel companies began using advertorials, or ads disguised as editorials. Eventually, they used advertorials to promote doubt about climate science.

Both native ads and advertorials are cited in a growing number of lawsuits that accuse fossil fuel companies of deceiving the public about their role in climate change. The New York Times’ “Unexpected Energy” campaign for Exxon was cited in a lawsuit brought by the Massachusetts attorney general against the oil company. Another, created by the Washington Post for Shell, was cited in a lawsuit brought by New Jersey’s attorney general.

“This should be of concern to news organizations that own in-house content studios,” Amazeen warns in her book. “Although the Federal Trade Commission guidelines on native advertising only briefly mention liability, they do state that content creators are not immune from liability simply because they represent a client.”

Today, Americans are growing less confident in companies’ promises to address climate change, according to a new survey Amazeen co-authored. But even if the ads themselves don’t work to change the narrative, their existence degrades readers’ trust in the real reporting, Amazeen found. She posits that may be a “secondary benefit” for oil companies sponsoring climate-related newsletters, like Politico’s Morning Energy and The Washington Post’s Climate 202.

Native ads can also lead to an “agenda-cutting effect,” where outlets report less on their sponsors — a win-win for corporate interests that may be causing harm to the public. In another analysis of content across five years from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, Amazeen found that just over half the time when media outlets created branded content for corporate clients, their coverage of that corporation steeply declined. (Abramson said that during her tenure at the Times, “never once was a big advertiser able to influence anything to do with news coverage.”)

Still, evidence of that dynamic should be especially concerning as the climate crisis gets less and less airtime from politicians and media outlets, all while climate disasters get worse, tipping points whiz by, and oil companies produce more oil despite a global glut. Mainstream media outlets laying off climate staff en masse and failing to cover the story while inviting more corporate money and influence on-board, even while the public largely demands climate action, are helping to facilitate that silence.

As climate journalist Amy Westervelt writes, “Getting governments to take the action citizens want on climate requires closing the perception gap, something the media may have helped to create in the first place, but is also uniquely positioned to fix.”

Amazeen takes a similar stance, positioning climate change as just one of the major issues where the media has prioritized corporations over the public. “They’re squandering this opportunity” to help arm the people with the information they need to participate in democracy, she said.

While Amazeen maintained that media outlets should stop creating native advertisements altogether and “figure out how to keep [themselves] financially solvent without deceiving your readers,” she suggested that better standardization of required disclosures would at least help alleviate the problem. She also said outlets should be required to make their native ads available in a repository akin to Meta’s Ad Library. In the meantime, she is building her own repository for native ads promoting fossil fuel interests as part of her ongoing research into climate disinformation.

If you come across such an ad, you can deposit it into Amazeen’s repository here. Her book, Content Confusion, is available from the MIT Press.

Native is a killer for trust and has long been and it’s getting worse. Every media room has a “content” desk that is essentially an arm of the sales team. It’s insidious. But in an age of affiliate marketing and influencers and “everything is content” it’s the entire ecosystem that is poisoning itself.

I believe that nonsensical and false TV ads are the root cause of all the lies that the less informed are bombarded with every day is the problem here. Trump is the proof.

We should demand a "truth-in-advertising" set of laws to regulate what can be legally used to get people to believe in and buy their products. Example: Nationwide is NOT on your side. Their first goal is to scam as many people as they can for huge profits so they can put their name on another skyscraper, sports venue, or street, etc.