How the petrochemical industry is gaslighting Southeast Texas

Across the Texas Gulf Coast, some residents say the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry is trying to green-and-whitewash its destructive presence in their communities.

Emily Sanders is senior reporter for ExxonKnews.

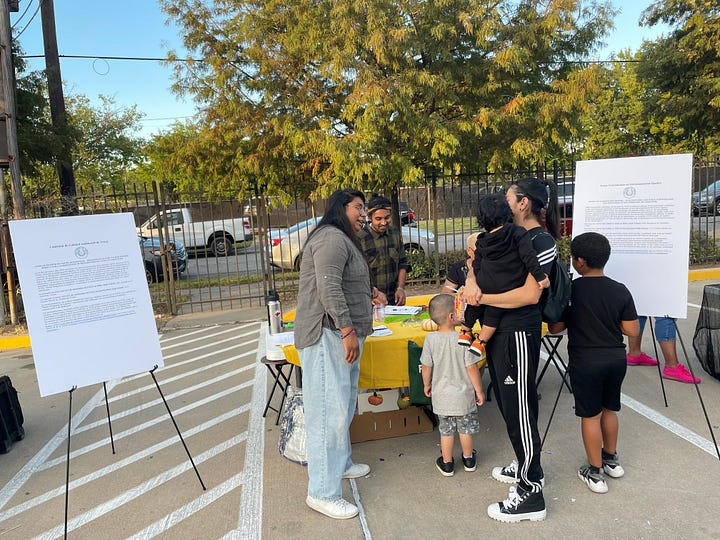

Yvette Arellano and their team had knocked on at least 180 doors in Manchester, Texas. A public hearing was coming up on December 12, 2022, for a permit renewal of oil giant Valero Energy Partners’ tank hub in Manchester, and Arellano, director of the Houston-based environmental justice organization Fenceline Watch, wanted to make sure residents had a chance to speak up.

The community, a low-income, majority Spanish-speaking neighborhood in Houston’s East End, sits beneath two highways, a slew of industrial projects along the Houston Ship Channel, and more than a dozen oil and petrochemical facilities — including Valero’s Houston Refinery. During Hurricane Harvey, a submerged roof of a storage tank at the refinery released high concentrations of carcinogenic benzene and other pollutants for 11 days. As floodwaters rose and eventually blocked evacuation routes, the company did nothing to warn the public of the hazardous chemicals spewing into their air, Arellano said, and "significantly underestimated" the leak, according to the EPA. Even state and local officials who visited the refinery during the release reported feeling sick.

At the hearing, advocacy groups and residents would ask the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality for increased safety precautions over Valero’s operations, like the weatherization of tanks, publicly available data on benzene monitoring at the refinery’s fenceline, or a publicly transparent emergency response plan to prevent another disaster.

But when they got there, they were surprised to find they weren’t the only ones speaking on behalf of the community. Representatives from the city’s children’s museum, a local food bank, and a health clinic — all recipients of funding from Valero — were there to defend the company from additional oversight.

“They help us in making good decisions, making the right decisions for the community,” said Richard Torres, president and executive director of Christus Foundation for Healthcare, during the hearing. “Renewing its permit will allow them to continue to serve their customers and community, and continue with a demonstrated leadership role in helping address the healthcare needs in the underserved areas.” Valero gave the group $1 million to establish a new clinic in Houston’s East End, he explained.

That donation was announced six months after Hurricane Harvey.

"[Valero] told me about the meeting and I volunteered to go speak,” Torres told ExxonKnews in response to questions about his presence at the hearing. “I wanted to support them — they've always been very supportive of us, and I have worked on the corporate side and I know the importance of community support when it comes to regulatory issues. They're a good corporate citizen and I wanted for people to know the kind of business that is located there in Manchester," he said.

But Jennifer Hadayia, executive director of Air Alliance Houston, an advocacy group focusing on air quality, said Valero’s donation was part of a well-orchestrated PR show. “You’re donating to the clinics that are going to be taking care of the people you are sickening with your pollution,” said Hadayia. “The irony of that can't be lost on anyone.”

Manchester residents never got the safety measures they asked for at the hearing, Arellano said. But Valero got its permit, and the company went on to make a record $11.5 billion in profits that year. (Valero did not respond to requests for comment.)

As the fossil fuel industry plans to expand its operations along the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast, some community members say companies are eager to be seen as helping to solve problems that may result from their pollution. From petrochemical facilities branded as “low-carbon” to band-aid investments in community services, local advocates argue that the industry is strategically funding projects that will buoy its reputation while neutralizing community resistance to its continued pollution.

The Houston area already boats 618 chemical manufacturing establishments and is home to more than 44% of the total petrochemical manufacturing capacity in the U.S. Yet many more facilities are slated to be built in the region. A new report from the Environmental Integrity Project found that petrochemical majors have received nearly $9 billion in public subsidies since 2012 to build or expand plastic production facilities, many of them in communities of color across the Gulf Coast of Southeast Texas.

In the Harrisburg/Manchester neighborhood, where more than 96% of the population are people of color, approximately 90% of residents live within 1 mile of a chemical facility.

While oil and chemical companies’ footprint in the region is growing, so too is evidence of the industry’s “devastating harm” on the communities where they operate. A January report from human rights group Amnesty International found a pattern of “irresponsible operating practices by petrochemical companies along the Houston Ship Channel,” documenting thousands of air pollution violations associated with elevated cancers, respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses, and reproductive issues in fenceline communities. In 2023, there were at least seven petrochemical disasters, including six fires, along the Ship Channel, where “chemical disasters occur so frequently that there is a widely held belief that they are simply the cost of doing business.”

As Hadayia explained, Houston’s zoning laws are such that “you can pretty much put anything next to anything” — leading to schools, churches, playgrounds, and childcare and healthcare facilities all bordered by petrochemical plants belching toxic pollution.

While companies operating in these communities represent themselves as good neighbors, they continue to fight regulation of that pollution. Last week, the EPA issued a final rule to significantly reduce cancer-causing pollutants from chemical plants and expand requirements for fenceline monitoring — a move praised by community leaders along the Gulf Coast. But the American Chemistry Council, a trade association representing oil and chemical majors, criticized the EPA for basing its rulemaking on “inflated risks and speculative benefits.”

In 2015, Yvette Arellano was volunteering on a farm in Southeast Houston when they started developing discolored rashes all over their body. “There was this big plume of black smoke,” they said, coming from a TPC petrochemical facility less than 3 miles away.

It took five years to get the rashes under control, and they still flare up when Arellano documents chemical fires or pollution events. But their time working in polluted air left scars in more ways than one. In 2019, the results of a blood panel showed Arellano’s chances of having children were, they said, “slim to none.” (Reproductive issues, like skin rashes and burns, are strongly tied to petrochemical pollutants).

It was something Arellano couldn’t imagine in their own childhood — that the same companies that gave away free backpacks and pens at school, that funded local parades, could wreak such havoc.

“Our cities and municipalities have been co-opted by industry so much that the little dribble of resources that comes out intimidates people from speaking out,” Arellano said. “Now I’m a young person who should have the ability to have a family and that right has been completely stricken away.”

Arellano, whose parents immigrated to the Houston area from Mexico, envisions something more for East Houston — a place rich with Mexican-American culture and a history of resistance. “Unintentionally or intentionally,” they said, “we’re getting erased.”

Big Oil and chemical companies don’t just sponsor backpacks and parades in Texas — they're also increasingly investing in expensive, hazardous, and unproven technologies disguised as climate solutions, advocates say.

In Baytown, Texas, where ExxonMobil is already being sued by residents for toxic emissions from its oil refinery and petrochemical complex, the oil giant has started an “advanced recycling” facility that touts its ability to recycle 80 million pounds of plastic waste annually. At the City of Houston’s Earth Day Speakers Series event in 2023, Michelle Salim, an Advanced Recycling Program Manager at ExxonMobil, was featured at an event to “discuss recycling’s challenges and opportunities through new technologies such as advanced plastics recycling.”

But Exxon is using dubious accounting methods to claim plastic is being recycled at the plant and making questionable claims of the operation’s climate benefits. An October report from Beyond Plastics and the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) found that “no information was publicly available on how much plastic waste is being processed” at the facility. The report did find, however, that while advanced recycling facilities are not a viable solution to plastic waste, they regularly “release toxic emissions, create hazardous waste, and are prone to fires and explosions.”

“We all know it’s a way to prop up the petrochemical industry as more focus shifts to renewables, so they don’t end up being obsolete,” said Hadayia. But while these companies are “proposing expansions and new kinds of manufacturing that they claim is a public good, they really don’t tell the community what’s going on” at their existing facilities, she said. Hadayia’s organization, Houston Air Alliance, installs its own air monitors in refinery towns and trains residents to help read them.

ExxonMobil did not return requests for comment.

Perhaps nowhere is the juxtaposition of the industry’s investments in its social license to operate and its treatment of the communities where it does so as apparent as West Port Arthur, a predominantly Black community bordering Louisiana on the Texas Gulf Coast where petrochemical facilities are clustered on top of homes, churches, and schools.

On the first night of a January media briefing hosted by the nonprofit advocacy group Beyond Plastics in Port Arthur, a storm rolled into town. Heavy rain and cracks of thunder shook the hotel conference room where we gathered. The next morning, one attendee from New York showed up in the conference room covered in mysterious rashes — a common symptom of the local air quality. We were being given a tiny taste of daily life in Southeast Texas.

For community members who attended the conference, the storm brought up memories of Hurricane Harvey, which damaged or destroyed an estimated 80% of housing in the already low-income community. Driving around West Port Arthur on a “toxic tour” of the facilities, we saw battered and empty homes, some with remnants of blue tarps still tethered to their roofs.

Our guide, John Beard, spent almost 40 years working for ExxonMobil as a refinery operator, industrial firefighter, and hazardous materials handler at a nearby petrochemical complex before turning to activism and public service. Today, he is director of the local advocacy group Port Arthur Community Action Network (PA-CAN).

West Port Arthur is surrounded by oil and petrochemical facilities with long histories of documented pollution violations, including Motiva, Valero, Oxbow, ChevronPhillips. Beard says many of the properties have been devalued by polluting infrastructure and hurricanes, and that his neighbors — many of them elderly — aren’t able to leave because they can’t get a fair price for their homes.

We stopped outside of Valero’s refinery — half a mile from where Beard was raised and still lives. The facility has a history of sulfur dioxide emission violations, for which it was sued by the Texas attorney general in 2019. Those emissions (and others from nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds at the complex) can lead to respiratory illness — which is prevalent in Port Arthur, along with higher rates of kidney disease, cancer, and double the national average of childhood asthma.

Shortly after Hurricane Harvey in 2017, a fire at the refinery released a million pounds of emissions including sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter into the air. It wasn’t the first time: a decade earlier, Beard recalled, a massive release of hydrogen sulfide at Valero’s facility sent dozens of people to the hospital.

“We’re dead men walking here in Port Arthur,” Beard later told me. “The petrochemical industry is sacrificing our lives for their profits.”

But the company’s web page and statements from officials at its Port Arthur refinery tell a very different story: one of a good corporate neighbor making the community a better place.

In November, Valero’s Port Arthur management announced that it would donate $1 million to local children’s charities. “We’re proud to partner with these agencies and work together to improve children’s lives right here in Southeast Texas,” said Mark Skobel, vice president and general manager of the Valero Port Arthur Refinery.

Valero’s web page for its Port Arthur refinery cites “environmentally responsible operations” including a federally-backed carbon capture plant that opened there in 2013 — an example of what Beard called a “false solution in order to get tax incentives and also look socially responsible so they can increase production and continue to do business as usual.”

“It’s time for us to change and transition — and not transition to plastics,” Beard said. “Our lives should matter, and matter enough.”