Exxon’s risky CO₂ pipeline passes far too close to homes and businesses, Louisiana residents say

Experts and advocates decry hazards to people and lack of regulations, transparency

This piece is being co-published with The Lens, the New Orleans area’s first nonprofit, nonpartisan public-interest newsroom, dedicated to unique investigative and explanatory journalism.

London Toussaint, 8, points to the sugarcane field just behind her home.

“That’s where we play at,” she says, “Me and Lyric, my best friend.”

For children in rural St. James Parish, Louisiana — which straddles the Mississippi, about an hour upriver from New Orleans — the sugarcane fields that dot the area are perfect for games of hide-and-go-seek, running down the rows between the tall plants.

They like to play there during the cooler months, said London’s mother, Nylah Toussaint, as she hoisted her one-year-old daughter Dream up to her hip. Nearby, there’s a berry tree they like to sit under.

But unknown to the Toussaints, Exxon has quietly pushed through a plan to bury a controversial pipeline in their playing field — one that experts say will be seriously under-regulated, and far too close to homes like the Toussaints’.

“We wasn’t informed,” Nylah Toussaint said, frowning. “I never knew anything about a pipeline.”

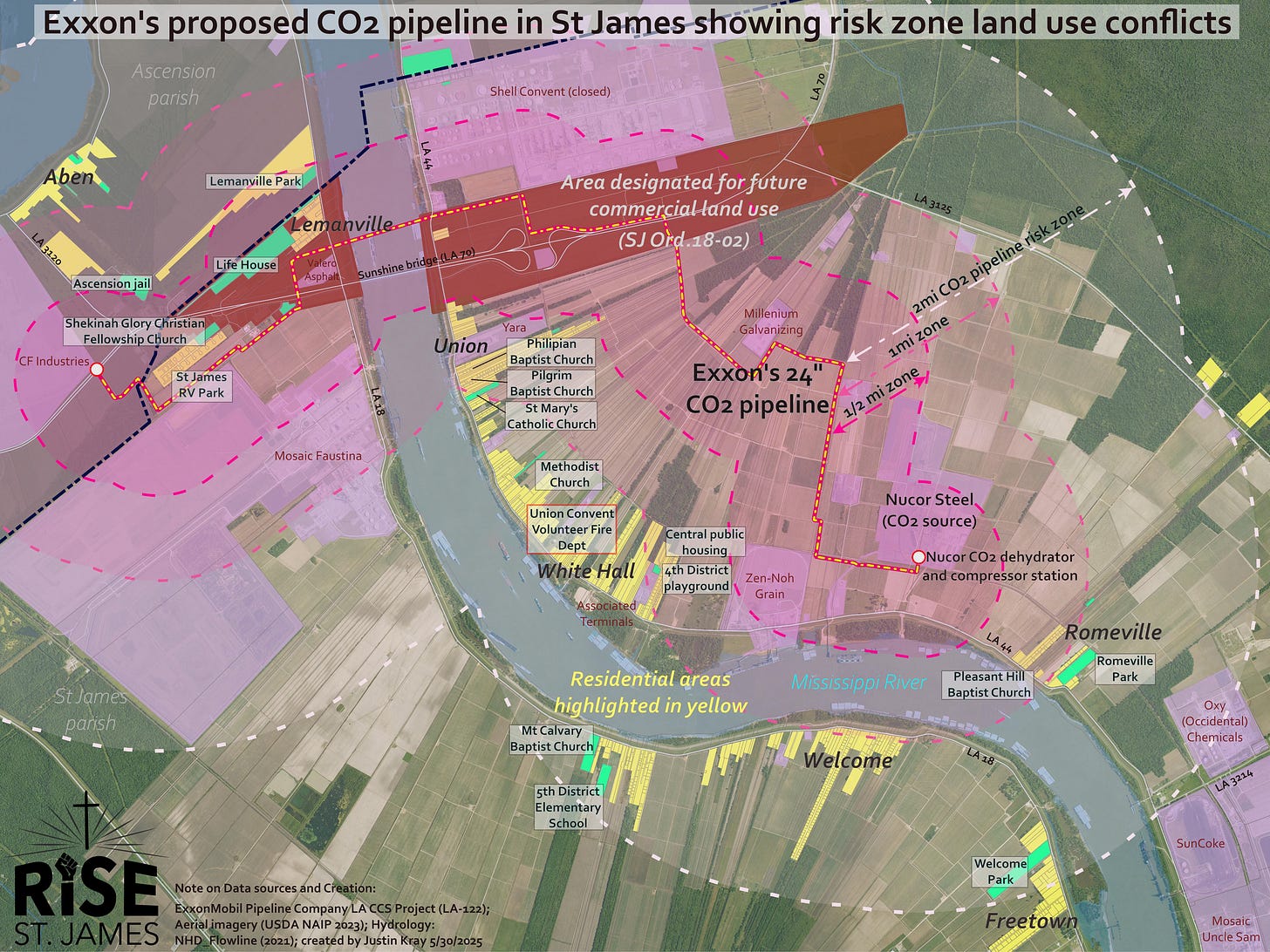

With little public input, Exxon received local government approval to install the pipeline here, in the area widely known as “Cancer Alley,” the 85-mile span of the Mississippi River lined by nearly 200 petrochemical plants, stretching from New Orleans to Baton Rouge. The new eight-mile, 24-inch-wide pipeline would transport highly-compressed carbon dioxide through this part of St. James Parish, passing just 155 feet from a business and 355 feet from the nearest residence.

The proximity might be worrisome for any pipeline, but CO₂ pipelines are particularly concerning, critics say, because carbon dioxide is a transparent, odorless asphyxiant that doesn’t dissipate like natural gas.

Pipeline will feed CO₂ into the nation’s fast-growing carbon-capture transport network

The CO₂ running through the eight-mile St. James pipeline will be captured within the parish, from the Nucor steel manufacturing plant in Convent. It will be piped northwest from Convent, will turn west to cross underneath the Mississippi River, and then pass near a commercial area of St. James until it reaches CF Industries, in Donaldsonville, in neighboring Ascension Parish. There, it will be fed into an existing carbon capture and transport network.

The Toussaint family lives along that pipeline’s path in St. James, where rental homes, apartments, and an RV park surround the quiet Sugar Hill residential neighborhood.

St. James Parish councilmembers waved through the proposal, which is now in the hands of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its streamlined permitting process for CO₂ pipelines.

It’s all part of a national CO₂ pipeline buildout that is accelerating under Trump.

Industry representatives say carbon capture — when CO₂ is captured from smokestacks and other industrial processes and piped elsewhere — reduces emissions. But across the country, residents, advocates and safety experts are raising the alarm about planned carbon pipelines’ proximity to people, the potential for disaster if an incident were to occur — and the lack of public input, as local boards rubberstamp the projects, like the St. James Parish Council did in July.

In 2023, Exxon purchased carbon dioxide pipeline operator Denbury, and now owns most of the carbon pipeline infrastructure in Louisiana. The state has become the epicenter for deploying carbon capture technology, as petrochemical companies claim to use it to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Thanks to the new pipeline, Nucor will be able to sell “low-carbon steel” for higher prices. Exxon originally suggested the CO₂ captured from Nucor would be transported 100 miles away and stored underground in Vermilion Parish.

But the Trump administration recently increased tax credits that incentivize using captured carbon to drill for more oil in a process known as enhanced oil recovery, where companies inject high-pressure CO₂ underground to force out more crude oil. Since that change, Exxon reportedly indicated to the St James Planning Commission that the CO₂ will instead be transported to Hastings, Texas, for enhanced oil recovery.

Internally, Exxon officials have assumed that carbon capture and storage won’t be effectively deployed at a large scale anytime in the near future to reduce emissions. Instead, advocates warn that CCS increases net emissions. Still, the corporation continues to market it as a climate solution to the public, spending at least $50 million to date lobbying for the technology’s expansion.

For residents, part of a lifelong fight against industry

Barbara Washington, 74, can trace her family roots back to emancipation here, in the small river town of Romeville that neighbors Convent.

Once primarily a farming town, Romeville is now blanketed by pollution from chemical facilities and oil and gas infrastructure. It sits in the center of Cancer Alley.

After cancer and respiratory illnesses hit dozens of her family members, friends, and neighbors, Washington saw ties between the medical problems and high rates of pollution. A few years ago, she co-founded the St. James-based environmental justice group Inclusive Louisiana, to organize local residents fighting industrial development.

Washington can see the Nucor Steel facility and its smokestacks from the window of her home. Soon, it will mark the start of Exxon’s new CO₂ pipeline.

Carbon capture projects will exacerbate the health problems here, Washington fears, by expanding industry’s license to pollute by claiming to be low-carbon. She worries about Exxon placing CO₂ pipelines so near to her community, and fears it will put people at further risk.

Ashley Gaignard, an environmental advocate with Rural Roots Louisiana in Ascension Parish, where the St. James pipeline would terminate, expressed similar concerns. Gaignard has fought several carbon capture projects in her region and doubts the confident claims of industry, especially given their track record of toxic pollution and recent buyout proposals in the parish.

“They're going to build our community out of the area,” she said. “They're going to be the reason that we won't have a community. I just wish that our political leaders could walk away with some integrity and do the right thing.”

Exxon is trying to skirt public feedback on the plan, advocates believe.

The parish council gave residents less than one day’s notice for Exxon’s appeal hearing, when the company managed to move the pipeline proposal forward after failing to get approval from the local planning commission. “We get in the room and it is full of industry people, people from out of the area, like they had weeks of notice to get their scripts and everything together,” said Jack Green, campaign manager at local advocacy group Rise St. James.

Gail LeBoeuf, who co-founded Inclusive Louisiana with Washington, had the same impression. “It sounds like a public hearing here tonight and only Exxon people knew about it,” she told the council.

Earlier in the year, the legal advocacy nonprofit Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) had notified the parish council that they may be violating local and state conflict of interest laws. Because Parish Council President Pete Dufresne owns several properties in the path of the proposed pipeline, he stands to benefit financially from servitude agreements with Exxon. CCR never received a response.

The parish council did not respond to requests for comment.

Lifelong residents like Washington and LeBoeuf harbor doubts that the community is prepared. For instance, like many other rural communities facing new carbon dioxide pipelines, the St. James Fire Department is volunteer-run. Even now, Washington said, residents sometimes wait hours before firefighters arrive on scene.

Washington worries that the volunteer firefighters are not equipped for a carbon dioxide rupture. “God forbid that any explosion would happen — we know if there was a rupture, that it would be devastating for us,” she said. “We would be a little wiped-out town.”

CO₂ pipeline rupture and emergency unpreparedness

When another carbon dioxide pipeline ruptured in 2020 near Satartia, Mississippi, a cloud of gas flowed into the small town, displacing oxygen, choking the engines of emergency vehicles, and initially bewildering first responders.

At least 45 people sought medical attention at hospitals. Some residents still reported symptoms of hypoxic brain injury years later.

After that incident, advocates and pipeline safety experts pushed for updated regulations for carbon dioxide pipelines from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). Regulations proposed in the final days of the Biden administration would have mandated new leak detection requirements and established emergency planning zones for two miles surrounding the pipelines, among other rules. But they were all scuttled by Trump earlier this year.

The disaster in Satartia highlighted grave concerns over emergency responders’ ability to respond to CO₂ pipeline incidents.

The pipeline operator, Denbury, didn’t notify Sataria emergency responders about a leak. Instead, emergency crews had to call Denbury themselves to learn that the gas cloud contained CO₂. Most did not yet fully understand the impact that carbon dioxide can have on people and even emergency vehicles. First responders who dealt with the incident have said that electric emergency response vehicles are necessary near carbon dioxide pipelines, since CO₂ choked the engines of their vehicles, rendering them inoperable.

Federal regulators investigating the rupture found that Denbury had committed several violations. The company had failed to notify first responders that the pipeline was experiencing a pressure loss. And in its dispersion model, which would inform emergency responses, the company had underestimated the areas that could be impacted by such a rupture.

Denbury paid a $2.8 million penalty. Then, earlier this year, PHMSA proposed another $2.4 million fine against Denbury after its workers allegedly harassed federal inspectors who came to monitor the replacement of the damaged section of pipeline.

Louisiana CO₂ pipeline threats

Near the town of Sulphur, in southwest Louisiana, where Exxon has another CO₂ pipeline, Fire Chief Todd Parker is in regular contact with the company, and his firefighters are attending trainings funded by Exxon to prepare them for how to respond to CO₂ leaks. The training curriculum is based in part on guidance from the American Petroleum Institute.

Exxon’s pipeline near Sulphur sprung a small leak last year. Exxon was failing to monitor the pipeline — the facility’s surveillance camera wasn’t working — and operators didn’t arrive to fix the leak for more than two hours, the Guardian reported. Afterwards, multiple local residents reported they had only learned of the leak through social media.

The bigger picture behind these incidents are not lost on residents of St. James.

If Exxon’s pipeline in St. James ruptured, the CO₂ could reach people’s homes in a fraction of the distance it traveled in Mississippi.

And as a state, Louisiana has a poor track record.

In a 2022 analysis, the nonprofit Healthy Gulf found that Louisiana has more high-pressure gas pipeline incidents per mile than any other part of the country — more than twice the national average of oil and gas pipeline incidents per mile.

“It's a lot more than I believe the St. James Parish emergency response can handle even though they have publicly said they can — we would like to see it in writing,” said Scott Eustis, a science director with Healthy Gulf.

Earlier this year, at three hearings with the St. James Parish Planning Commission, the municipal body that would have to rezone land for industrial use along the pipeline route, Eustis and other local environmental advocates raised concerns about emergency preparedness and about the risk of an incident with this particular pipeline route.

The pipeline would cross tectonic fault lines, where plates shift, Eustis said. It would also run under levees that shift when the river is at flood stage. “These pipelines are subject to a lot of forces and fatigue that you don’t see in other parts of even Louisiana,” Eustis said.

In response to the technical concerns, Exxon added a few safety precautions to its proposal. Company officials promised to build the pipeline seven feet underground, rather than four. They also added an extra automated shut-off valve to isolate the gas in the event of a rupture.

But ensuring safety “depends on a rapid response to a leak,” said Ted Schettler, science director at Science and Environmental Health Network, “which did not occur in Satartia or Sulphur.”

Exxon representatives downplayed concerns. If CO₂ did rupture from the pipeline, “you’re going to be able to see it, and you’re going to be able to walk away from it,” Exxon representative Michael Smith told the parish council.

Threatening Louisiana communities

The St. James pipeline threatens places where people live, work, worship, and play, residents say. It runs less than 350 yards from Nylah Toussaint’s neighborhood, Sugar Hill Crossing; along with the nearby Sugar Hill RV Park; a juvenile detention center; at least one playground; and a church. It would pass a half mile or less from the Ascension Parish Jail and a second church.

Many of Toussaint’s neighbors have health problems and are unable to move quickly on their own, she said. “They’ve got a lot of old people who use oxygen and all kinds of medical problems, people that go to dialysis,” she said, noting that many are disabled or don’t have cars.

Those without means to evacuate would be transported by bus, said Eric Deroche, Director of Emergency Preparedness in St. James Parish. But St. James Emergency Management doesn’t own any electric emergency response vehicles, as recommended by Mississippi officials.

Though St. James stopped using its community air sirens because of high operational costs, the parish’s phone emergency alert system would warn people in the area, even if they aren’t signed up for emergency alerts, he said. Exxon is paying for the parish to purchase gas meters that would detect CO₂, Deroche said, and has facilitated third-party training on CO₂ leaks for local emergency responders. But the department doesn’t yet have a copy of Exxon’s emergency response plan, which isn’t required on file until next year, when the pipeline goes into operation.

Deroche also has not received Exxon’s dispersion models, which show the potential dispersion of high concentrations of carbon dioxide in the event of a rupture. Though those models, if accurate, could help emergency personnel and communities prepare for possible incidents, Exxon officials argued that such models would “provide misleading information to the public” and pose a security risk.

In a statement, an ExxonMobil spokesperson said, “These projects take years of planning and testing, with strong oversight and round-the-clock monitoring. CO₂ pipelines have a good safety record, and in the rare case of an emergency, we’ve taken steps to make sure local first responders are trained and ready to act.”

Unlike states and municipalities, federal regulators at PHMSA cannot enact distance requirements for pipelines. Louisiana representatives introduced legislation for carbon dioxide pipelines in the state, which included the creation of distance requirements from residences, but the bills failed to move out of committee. Some Louisiana parishes also tried to pass local carbon capture laws and moratoriums, only to find them blocked in the courts. In July, Exxon sued Allen Parish over a local ordinance that would have required local permits for carbon capture projects. The parish then rescinded the ordinance.

Though industry officials report confidence in CO₂ pipelines, the risks are too great, said Gaignard, of Rural Roots Louisiana.

“They claim they’ve been doing these projects for years and years, but they have never ran carbon capture pipelines under residential communities before,” she said.