A 3M whistleblower’s quest to counter corporate deception

Chemist and “forever chemicals” whistleblower Kris Hansen talks about her ongoing mission to expose a powerful company’s coverup.

Former fossil fuel industry scientists are increasingly speaking out about how oil executives covered up their operations’ harm to the climate. Their testimony has helped fuel a public reckoning and lawsuits.

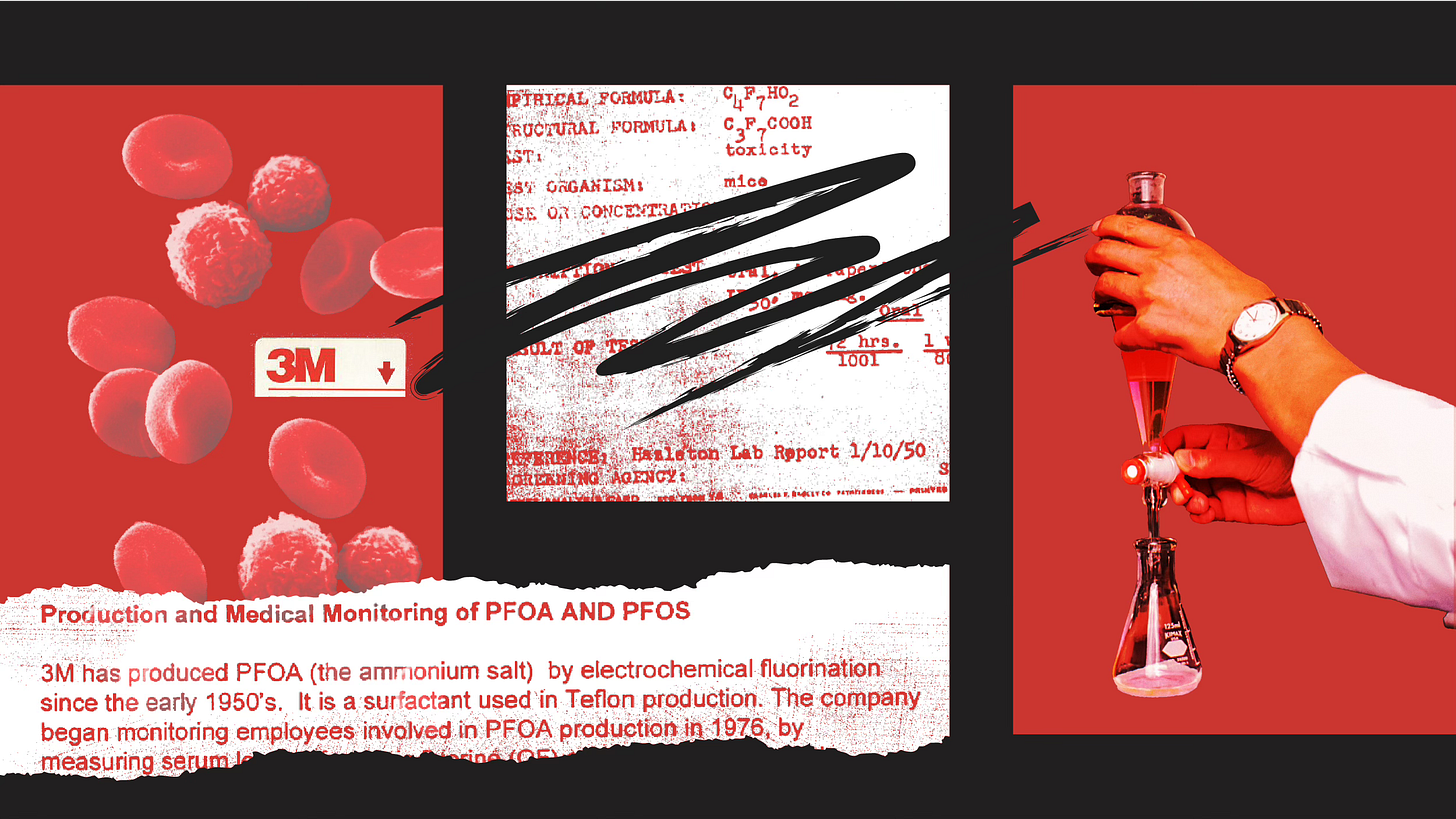

Kris Hansen is now working to shed similar light on her experiences working as a chemist for 3M, a company that has manufactured a host of products containing toxic “forever chemicals” known as PFAS. In an in-depth investigation by ProPublica journalist Sharon Lerner, Hansen revealed how the company buried and undermined her research in the late 1990s, which showed conclusively that the chemicals 3M was using — PFOS, a type of PFAS — had become ubiquitous in human blood.

Years of reporting and lawsuits have helped show that while 3M told the public (and Hansen) that PFOS did not pose a public health threat, the company knew they were toxic. While promising to phase out PFAS, 3M still claims its products containing the “forever chemicals” are safe, despite the chemicals’ well-documented link to cancer and reproductive harms.

The company told ProPublica that it was “‘proactively managing PFAS,’ and that 3M’s approach to the chemicals has evolved along with ‘the science and technology of PFAS, societal and regulatory expectations, and our expectations of ourselves.’” The statement echoes one made at a 2021 congressional hearing into climate disinformation by ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods, who said that “As science has evolved and developed, our understanding of the science has evolved and developed.” But like fossil fuel companies, chemical manufacturers and industry trade associations have nonetheless continued to fight regulations of their products. In May, Trump’s EPA began rolling back PFAS regulations.

Hansen lives in Afton, Minnesota, a short drive from 3M’s headquarters in St. Paul. More than a decade after the state entered into a settlement agreement with 3M, contamination of PFAS in the east metro area of the Twin Cities’ groundwater is still increasing — and Afton has some of the most contaminated wells there.

I spoke with Hansen about the rise of science denial, growing threats to accountability, and her quest to reveal the strategies corporations use to manufacture doubt. Our interview, lightly edited for length and clarity, is below.

It’s been just over a year since Sharon Lerner’s piece came out, and recently, you’ve started publishing more of your experiences at 3M and documents exposing the company’s attempts to conceal the science of PFOS. What’s inspiring you to keep speaking out?

I want to make sure that communities, particularly communities that are looking at trying to recoup costs associated with cleaning up their own drinking water, have access to and an awareness of all of those documents — so that if they're litigating, they have the best information that they can to do so. And my experience as a chemist but also as someone who worked at 3M during that time gives me some insights into those documents and into the people who wrote them, the dynamics and what else was going on.

My second purpose is that I feel that this whole discussion around the manufacture of doubt by industry is one that is super relevant and not as well understood and discussed as it should be. I hope that in talking about my own experiences and those documents, I can highlight more examples of industry manufacturing doubt in a way that other scientists or community members can look with skepticism at what they are being told by industries.

There have been a number of lawsuits that claim 3M hid the dangers of their products from the public, which have revealed even more evidence. 3M has settled some of them but never actually admitted fault. Have the documents revealed during those lawsuits been helpful for your own understanding of what happened or in other ways?

Super helpful, for two reasons. One, for 3M, this cover up started extensively in 1975 when I was six years old, so I don't have personal inside knowledge of 3M in 1975 — but by looking at those documents and combining that with my scientific background, I can see what was going on between 3M executives and some of the scientists. So the documents are very useful in helping me understand what happened before I came to 3M in 1996.

The other perspective that they share, of course, is the conversations that were being had by people at the executive level. I was a mid level scientist, and certainly there were a lot of conversations that were happening that didn't include me, so being able to see those documents now and seeing how they were looking at data that I was collecting, and making decisions about how to present that to the EPA or to the public — to me, that is very, very enlightening in terms of understanding the strategies they were using to control the narrative around PFAS contamination.

How has 3M shifted the way it talks about these chemicals and its supposed plans to stop producing them?

Their messaging has changed from saying there is no harm from these chemicals to more recently, they've said science is advancing. So they've kind of dropped that line about there's no health effects related to these chemicals. I do hear more from that industry who are saying yes, [these chemicals] last forever, but they're very important in all of these things that we really need.

There are alternatives available for almost all PFAS applications. Sometimes those alternative materials cost more to produce, but cost is not a characteristic of utility. When you think of the environmental and public health costs associated with PFAS, investing more in the production of a safer, cleaner material has huge economic upsides. Ask any community that has to invest in a wastewater treatment facility designed to remove PFAS: huge expense.

That’s of course also what the oil and gas industry says about their products — that we need them in society — and what they leave out is that it’s energy we need, which could come from even cheaper renewable sources. Are you seeing other industries using the playbook you’ve seen used by chemical manufacturers?

Well, oil and gas is the big one, and the denial within the corporations of their scientists’ data, and the executives making the decision to to hide that data, to not share that data, to downplay that data, to ostracize those scientists — that’s a very obvious example, and I think it's a very close cousin to what we see in the chemical industry. The story that really struck me and kind of got me moving on this was the story about asbestos in talc from Johnson & Johnson. It is heart-wrenching reading about the toxic effects of asbestos in talc that women used for their whole lives. They used it on their children. They used it on themselves, and then, they ended up with ovarian cancer. And when you look at the decisions that were made inside Johnson & Johnson about how closely to look for asbestos, and then, like, stop looking, don't look any further, and the messaging that went out about the risks associated with that. That's an example that really hits home, because I feel like the talc that women use after bathing and that they use on their children is such an intimate product. To have a corporation not take the necessary steps to protect the consumer and to make decisions to put the consumer at risk so that they can earn more profit is sickening, but it is again, very similar to what we see in the chemical industry.

[Note: Johnson & Johnson continues to state that “Decades of independent scientific testing have confirmed that our products are safe, do not contain asbestos and do not cause cancer” and that jury verdicts against them are predicated on “junk science.”]

We’re in an environment where disinformation and the rejection of science is coming not just from companies but even the U.S. federal scientific and regulatory agencies that are supposed to be overseeing these companies. Last week, President Trump’s EPA revealed plans to revoke the “endangerment finding,” the scientific conclusion that greenhouse gases endanger human health. Are there any lessons you've learned that might apply to people encountering disinformation in their workplaces right now?

It is, again, heartbreaking. I think in normal times, we can say that you have legal protections and you can't suffer retribution for reporting something. And I don't think that that's true right now in our government.

How I feel like I made my impact and why I became problematic at 3M is that, as I found out information that was concerning, I shared it. I shared it up the chain, but I also shared it with my peers and colleagues, and I wrote a lot of reports, put it down in writing, and I feel like when that data was documented, and when it was shared, it became much harder to cover up or to control the narrative associated with it. To the degree that I was at all effective in doing anything about my situation, I believe that it was that documentation and that dialogue with my peers, so that so many people knew what was going on that it was impossible to cover it up again.

I think a lot of people really feel like because disinformation is so prevalent and coming from the highest halls of power right now, accountability is impossible.

Yeah, I mean, that's honestly another reason why I feel like I want to write down my experiences right now. I feel compelled to state my truth and share my experiences so that at least it's something that the people who read have to take in, as they go and either fight against industry or consider how to deal with legislation. I hope it does give those communities the support that they need to go in and say, look, it's clear you are buying off an academic scientist to control the technical literature and to influence regulators. I think that that needs to be stated publicly, win or lose.

It becomes important to state your truth in the face of so many lies — I don't know what else to do, but it gives me some sense of a positive step.

What's it been like to see communities taking this company that you worked for to court after being on the inside for so long?

For many years, I believed the company's line that the chemicals were not toxic. And you know, even in my own community, when this was happening in the early to mid 2000s, I was kind of in denial. I put my head in the sand about it and said, “I don't want to get involved.” I think the community is overreacting. And it wasn't until 2021 that I really became aware of how much data there was and how significant the health effects were, across the board, on communities. And it radically changed my view of the corporation, a corporation that I had always thought was environmentally progressive and that I had been pretty proud to be a part of, to realizing, like, you're really no different than a corporation that hid the risks of cigarette smoking for decades, with all of these people who ended up dying from using your products.

Is there anything you think in particular the public should be focusing on that maybe is going under the radar?

I will say that one of the things that worries me most about this time is that the government has suddenly pulled back on all the funding for people who are independent researchers, which means they have magnified, essentially, the funding and the impact of industry to say what they want. So I think it's important to really understand when you see data, hear data that doesn't seem to fit with what you have always believed with respect to climate change or chemicals or asbestos, that you're looking at information that’s coming from industry. We need to not accept what we are being told simply because those are now the only voices that are receiving funding to generate science.

Learn more about best practices for whistleblowers from the National Whistleblower Center. Government whistleblowers can also go to Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility for guidance.